The stigma and discrimination associated with mental illness continue to blight the lives of those so diagnosed (Reference Corrigan and PennCorrigan & Penn, 1999; Reference Hayward and BrightHayward, 1997; Reference Crisp, Gelder and RixCrisp et al, 2000), despite extensive attempts to counter their effects (Reference Estroff, Penn and ToporekEstroff et al, 2004; Reference Sartorius and SchulzeSartorius & Schulze, 2005). Given that medical professionals are inevitably embedded in the fabric of society it is perhaps unsurprising that they can also hold stigmatising attitudes (Reference Üçok, Polat and SartoriusÜçok et al, 2004) and thus contribute to discrimination (Reference ByrneByrne, 1999; Reference Crisp, Gelder and RixCrisp et al, 2000). Indeed, surveys of mental health service users have revealed a relatively high prevalence of stigma and discrimination from healthcare professionals (Reference WahlWahl, 1999). Although several studies have found that medical students and doctors often regard psychiatric patients as difficult and unrewarding to treat (Reference Nielsen and EatonNielsen & Eaton, 1981; Reference Lawrie, Martin and McNeillLawrie et al, 1998), other research has reported that medical students’ attitudes towards mental illness and psychiatry become more positive following undergraduate training (Reference Creed and GoldbergCreed & Goldberg, 1987; Reference Singh, Baxter and StandenSingh et al, 1998), particularly where that training involves both patient contact and education about the effects of stigma (Reference Corrigan and PennCorrigan & Penn, 1999). Given the labour-intensive nature of existing anti-stigma interventions (Reference Pinfold, Toulmin and ThornicroftPinfold et al, 2003) and the power of audiovisual media to influence societal constructions of mental illness (Reference WahlWahl, 1995), researchers have postulated that documentary films depicting people diagnosed with mental health problems may offer a more efficient approach to reducing stigma and discrimination among student groups (Reference Penn, Chamberlin and MueserPenn et al, 2003). Indeed, existing research suggests that anti-stigma films can garner small and temporary improvements in specific areas such as social distance (Reference ChungChung, 2005; Reference Altindag, Yanik and ÜÇOKAltindag et al, 2006), though with little change in general attitudes (Reference Penn, Chamberlin and MueserPenn et al, 2003). This latter finding was attributed to the lack of an unambiguous disconfirmation of the mental illness stereotype within the film deployed (Reference Penn, Chamberlin and MueserPenn et al, 2003). We sought to determine the effects of an anti-stigma intervention based on films produced by mental health service users and combining both education and stereotype disconfirmation elements, on medical students’ attitudes to both serious mental illness and psychiatry.

Method

Study design

The study was conceived as a pilot project to refine the research methodology in anticipation of a larger scale trial. The two anti-stigma films used were made in partnership with non-statutory mental health organisations in Nottingham. Participants were 4th year medical undergraduates on their psychiatry training attachment.

We used a single-masked, randomised controlled trial design to compare a group who watched the intervention films with a group who watched a control film of the same format and length. We tested whether general attitudes to serious mental illness changed in the intervention group, whether the films changed specific attitudes concerning social distance, perceived dangerousness, and psychiatry. After baseline assessment, participants were randomised to either intervention or control groups and were then reassessed immediately after watching the films, and again at 8 weeks post-intervention. Ethical approval for the study was granted by the University of Nottingham Medical School research ethics committee. Written informed consent was not required as the project was an assessment of an educational intervention, although students were assured that their responses would have no influence on their grades or exam scores.

Intervention and control films

The first film, A Human Experience (Reference SmithSmith, 2005), was made in collaboration with service users at Rethink Nottingham. It is 15 min long and adopts a ‘talking head’ documentary style approach. Its content revolves around three mental health professionals (a teacher/researcher, a Mental Health Act Commissioner and a psychiatrist) discussing their experiences after being diagnosed with a serious mental illness (psychosis, schizophrenia and severe depression - all of which resulted in hospitalisation) and, in particular, their experiences of stigma and discrimination. The film challenges particular stereotyped beliefs, including dangerousness, inability to work and inability to maintain relationships, and mentions positive aspects of serious mental illness (such as the importance of the experience of mental distress in the forging of personal identity, a sense of overcoming adversity, the celebration of difference, and a formulation of mental distress as a deepening of lived experience). The second film, A Day in the Mind of… (Reference GreenGreen, 2005), was made by service users at Framework Housing Association Nottingham (a non-statutory organisation providing practical and emotional support for people experiencing mental distress and living in the community). It is 12 min long and adopts a first-person perspective throughout. Its narrative focuses on the subjective experience of psychosis over the course of a typical day. The film attempts to convey to the viewer the first-hand experience of being diagnosed with a serious mental illness, thereby challenging the stereotype of psychosis as a condition opaque to understanding. The control film was a 25-min documentary unrelated to mental illness or psychiatry and matched for visual format.

Outcome measures

-

• General attitudes to serious mental illness, as measured by the Attitudes Toward Serious Mental Illness Scale - Adolescent Version (Reference Watson, Miller and LyonsWatson et al, 2005), a 21-item validated measure of general attitudes in young people where higher scores indicate more negative attitudes.

-

• Perceived dangerousness, measured by the Dangerousness Scale (Reference Link and CullenLink & Cullen, 1986), a 5-item questionnaire with good internal consistency where ratings are made on a 5-point Likert scale, with higher scores indicating greater perceived dangerousness.

-

• Social distance, measured by the Social Distance Scale (Reference Penn, Tynan and DailyPenn et al, 1994), a 6-item questionnaire with good internal consistency where higher scores are indicative of a tendency to maintain a greater social distance from people diagnosed with a serious mental illness.

-

• Attitudes to psychiatry, measured by the Attitudes to Psychiatry Scale (Reference Burra, Kalin and LeichenerBurra et al, 1982), a well-validated 30-item questionnaire where higher scores indicate a more positive attitude towards psychiatry.

In addition to the main outcomes we also collected data on students’ previous contact with people diagnosed with a mental illness, affect at the time of assessment, and behavioural intentions towards such people.

Procedure

At baseline, on the first day of their psychiatric attachment, participants self-completed all four outcome measures. After baseline assessment, they were randomly allocated using a concealed randomisation method. Those randomised to the intervention group watched the two films on the second day of the attachment and the control group watched the control film. The outcome measures were repeated immediately post-intervention and at 8 weeks follow-up, at the end of the psychiatry attachment. Statistical analyses were undertaken by an independent researcher masked to allocation status and all participants were asked not to reveal their group allocation. They were analysed on an intention-to-treat basis, with Mann-Whitney U-tests employed to compare non-parametric data and independent samples t-tests used for parametric data. All results were corrected using the Bonferroni method to adjust for multiple comparisons. There was evidence that at baseline and post-intervention time points there had been confusion over the polarity of the rating scale for the Attitudes to Psychiatry questionnaire and scores were discarded for these time points. The rating scale was clarified in the final administration of the Attitudes to Psychiatry questionnaire and the 8 weeks follow-up scores were analysed.

Results

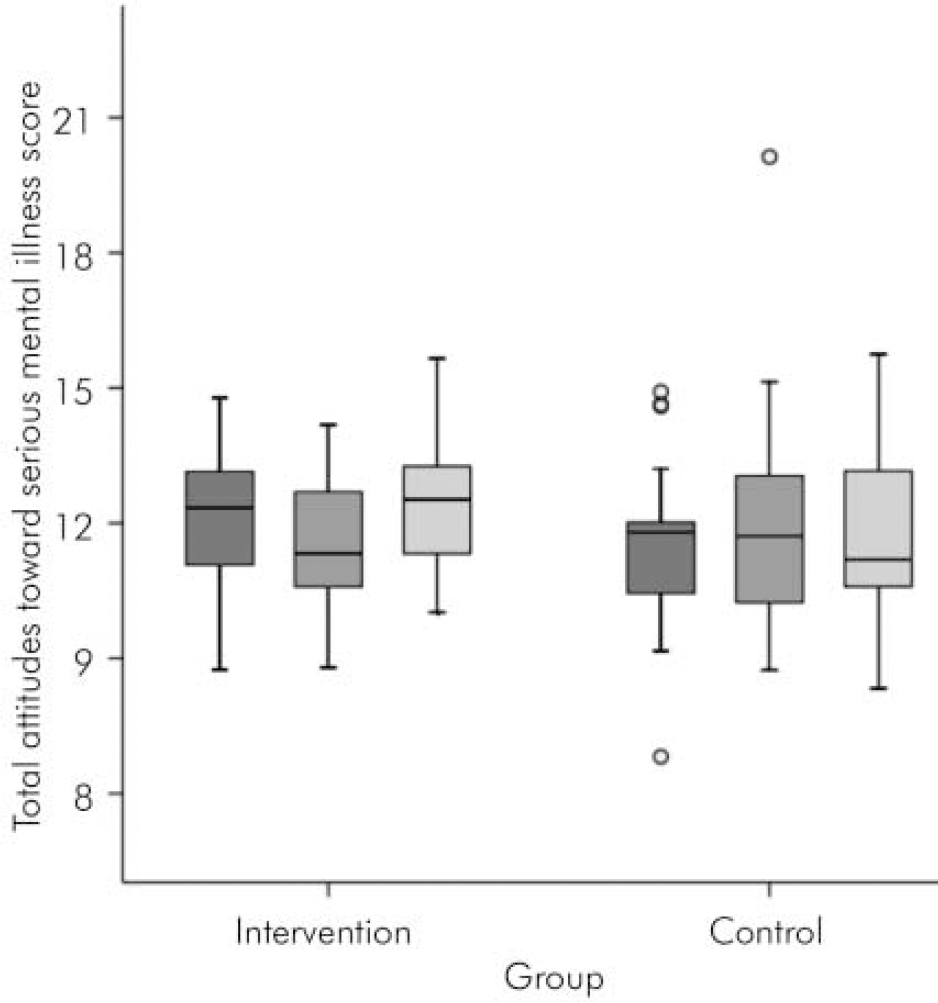

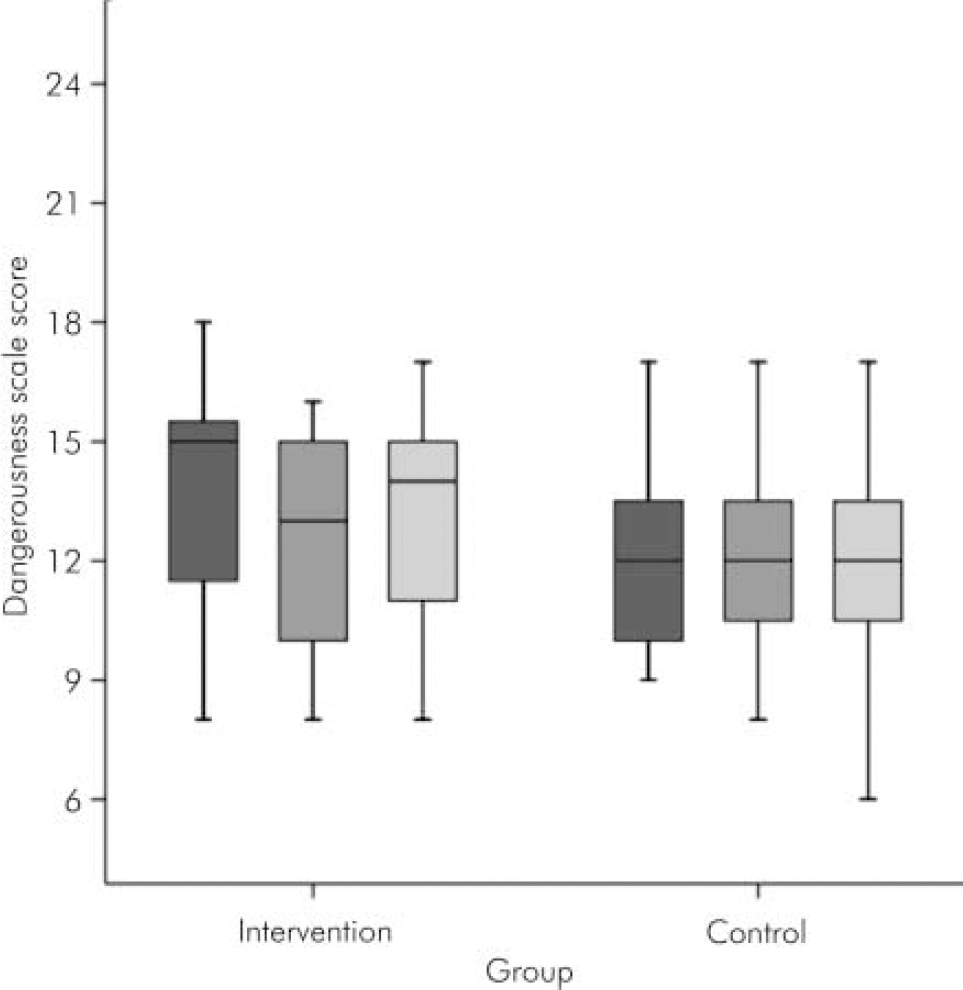

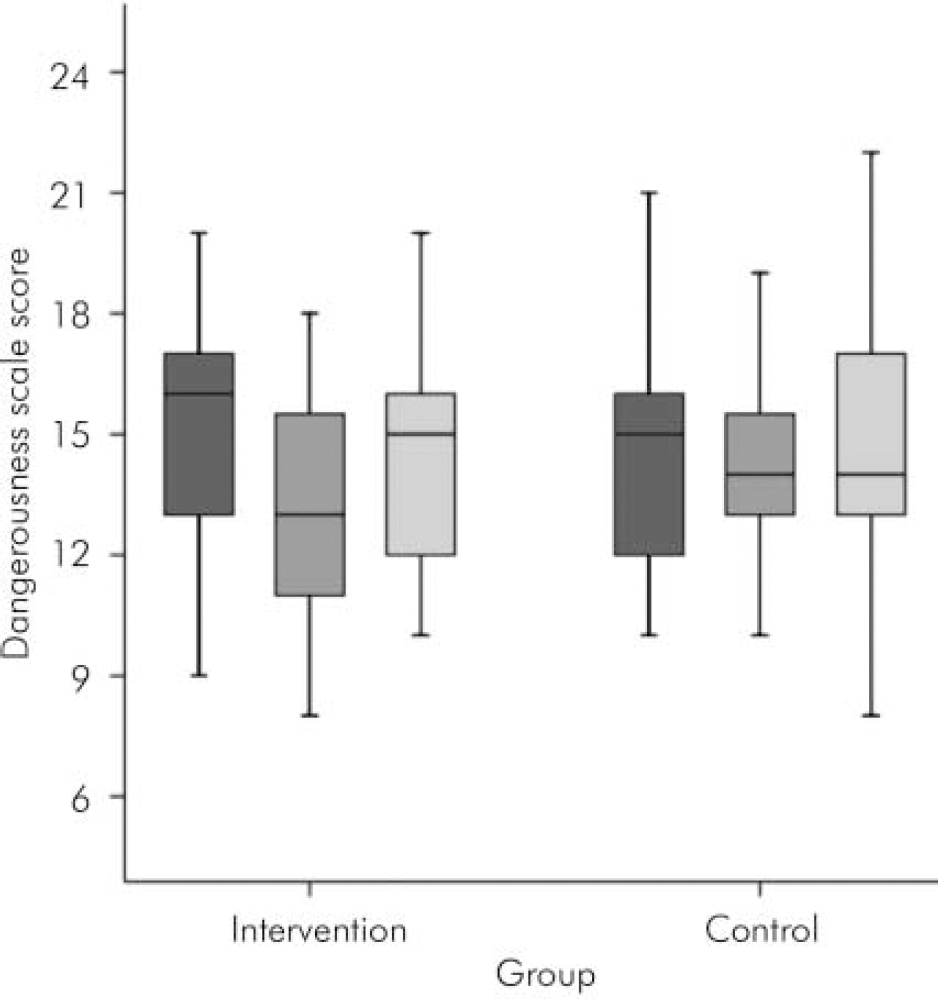

Although 82 medical students were eligible to participate in the trial, only 46 took part (56%) and were randomly allocated, 23 to each of the study arms (Fig. 1). Almost three-quarters of the sample were female (n=34; 74%) and the mean age was 21 years. A great majority (n=37; 80%) were White European; 28 (60%) had previous contact with a person diagnosed with a serious mental illness. There were no significant differences between the groups at any of the three assessment time points (Table 1). However, inspection of the data suggested some changes within groups and therefore for each group the scores for total attitudes to mental illness, dangerousness and social distance were analysed to determine whether they changed significantly over time, using a Friedman test. Post hoc Wilcoxon matched-pairs test was then used to determine between which time points the significant differences were located. Figure 2 shows that, with regard to total score for attitudes to mental illness, there was a significant change in score in the intervention group over the three time points (n=23, d.f.=2, P=0.026), with scores demonstrating a significant decrease from baseline to post-intervention (z=–2.614, P=0.009) suggesting that students’ attitudes were less stigmatising after the intervention. There was a trend towards significance for scores to increase from post-intervention to 8-week follow-up (z=–1.916, P=0.055), suggesting that this anti-stigma effect attenuated over time. Figure 3 demonstrates that there were significant changes in perceived dangerousness scores over the three time points in the intervention group (n=23, d.f.=2, P=0.062), with scores decreasing significantly from baseline to post-intervention (z=–2.782, P=0.005). There was no significant difference in scores from the post-intervention to 8-week follow-up time points, suggesting there was less attenuation than for general attitudes. Figure 4 shows that there was a significant change in social distance scores in the intervention group over the three time points (n=23, d.f.=2, P<0.0001), with a highly significant decrease in social distance from baseline to post-intervention (z=–3.546, P<0.0001). This suggests that the students’ inclination to be socially distant from people diagnosed with a serious mental illness lessened after watching the films, though this was not sustained at follow-up, with scores significantly increasing (z=–2.169, P=0.03). No significant differences in the scores for either total attitudes to mental illness, dangerousness, or social distance were found between each time point for the control group.

Table 1. Attitudinal and secondary outcome scores

| Scale | Intervention group (n=23) | Control group (n=23) |

|---|---|---|

| Attitudes Towards Serious | ||

| Mental Illness – Adolescent Version, median (IQR) | ||

| Baseline | 12.3 (11.0–13.2) | 11.8 (10.4–12.0) |

| Post-intervention | 11.3 (10.5–12.8) | 11.7 (9.9–13.6) |

| 8-week follow-up | 12.5 (11.3–13.3) | 11.2 (10.5–13.3) |

| Dangerousness, median (IQR) | ||

| Baseline | 15 (11–16) | 12 (10–14) |

| Post-intervention | 13 (10–15) | 12 (10–14) |

| 8-week follow-up | 14 (11–15) | 12 (10–14) |

| Social Distance, median (IQR) | ||

| Baseline | 16 (13–17) | 15 (11–16) |

| Post-intervention | 13 (11–16) | 14 (13–16) |

| 8-week follow-up | 15 (12–16) | 14 (13–17) |

| Attitudes to Psychiatry, mean (s.d.) | ||

| 8-week follow-up | 103.0 (15.3) | 111.1 (11.9) |

| Behavioural Intentions, median (IQR) | ||

| Baseline | 10 (8–13) | 12 (10–14) |

| Post-intervention | 9 (7–11) | 8 (8–10) |

| 8-week follow-up | 9 (8–10) | 8 (6–12) |

| Positive Affect Scale, median (IQR) | ||

| Baseline | 23 (19–26) | 29 (19–33) |

| Post intervention | 19 (15–26) | 24 (17–31) |

| 8-week follow-up | 22 (18–28) | 26 (19–30) |

| Negative Affect Scale, median (IQR) | ||

| Baseline | 12 (11–15) | 12 (11–14) |

| Post-intervention | 14 (12–17) | 11 (10–14) |

| 8-week follow-up | 18 (11–24) | 19 (12–25) |

Fig. 1. Study profile.

Fig. 2.

Within-group changes over time in total attitudes to serious mental illness scores for both intervention and control groups. ▪ Total attitudes toward serious mental illness score – baseline; ![]() Total attitudes toward serious mental illness score – post-intervention;

Total attitudes toward serious mental illness score – post-intervention; ![]() Total attitudes toward serious mental illness score – 8-week follow-up.

Total attitudes toward serious mental illness score – 8-week follow-up.

Fig. 3.

Within-group changes over time in perceived dangerousness scores for both intervention and control groups. ▪ Dangerousness score – baseline; ![]() Dangerousness score – post-intervention;

Dangerousness score – post-intervention; ![]() Dangerousness score – 8-week follow-up.

Dangerousness score – 8-week follow-up.

Discussion

On the whole, the study was successful, with several methodological problems being highlighted; not least of these being the fact that only 56% of potential participants eventually agreed to take part, thereby making the study vulnerable to type II error and introducing a selection bias. The effects of this lack of power are most tellingly revealed by the absence of any significant between-group differences (with any specific differences being overwhelmed by the much greater variance of individual participants’ characteristics in between group comparisons). However, this attrition rate compares favourably with those of some recent reports of randomised controlled trials in the mainstream psychiatric literature (Reference Wykes, Reeder and LandauWykes et al, 2007). Strengths of the study were the use of self-report questionnaires and data analysis masked to group membership which both served to minimise possible assessment bias.

Comparisons with existing normative data (derived in the main from US studies) suggest that, at baseline, participants in the present study both held more stigmatising attitudes towards serious mental illness and were more inclined to maintain social distance from people diagnosed with such illness (Reference Watson, Miller and LyonsWatson et al, 2005; Reference Penn, Tynan and DailyPenn et al, 1994) than the general population, but they also appeared to view them as less dangerous (Reference Link and CullenLink & Cullen, 1986). Although the possibility of confounding caused by differences in sociocultural context must be considered when interpreting research results, it is unlikely that cultural differences would have wholly accounted for these discrepancies. The participants maintained attitudes to psychiatry consonant with previous evaluations of medical students in Nottingham (Reference Singh, Baxter and StandenSingh et al, 1998). The former findings appear to be supported by research examining the extent to which mental health professionals stigmatise their patients (Reference Lauber, Nordt and BraunshweigLauber et al, 2006). Interestingly, the latter finding would appear to be at odds with the same work which found that mental health professionals are as likely as the general population to stereotype people diagnosed with mental illness as dangerous. This dissonance may reflect a selection bias, but the fact that this apparently ‘untypical’ group exists may be important, given that the intervention films were able to further reduce perceived dangerousness in a group with relatively benign extant attitudes. It was considered unfeasible to conduct subgroup analyses (such as by gender) because of the study's lack of power. Any subsequent research can remedy this and can also seek to examine the impact of the films on participants with more negative attitudes towards dangerousness.

Fig. 4.

Within-group changes over time in social distance scores for both intervention and control groups. ▪ Social distance scale score – baseline; ![]() Social distance scale score – post-intervention;

Social distance scale score – post-intervention; ![]() Social distance scale score – 8-week follow-up.

Social distance scale score – 8-week follow-up.

The within-group results, though highly provisional, are encouraging, suggesting that the intervention films may improve medical students’ attitudes to serious mental illness and decrease perceived dangerousness and social distance. However, our results suggest that the effects on general attitudes and social distance were attenuated over the 8-week attachment in psychiatry. Although no firm conclusions can be drawn from our data, this may have been due to the effects of the attachment, and any subsequent investigation may include both quantitative and qualitative attempts to understand how the films and experience of medical education within a psychiatric service interact. Further research is needed to investigate strategies to sustain these short-term improvements in students’ attitudes to people with serious mental illness, perhaps with an emphasis on the importance of the patient experience, as has been argued elsewhere (Reference Yang, Kleinman and LinkYang et al, 2007). Such strategies might also include ‘booster’ films designed to mitigate the corrosive effects of time and experience. A further substantive trial is currently being planned, with the intention of recruiting sufficient numbers of medical students to definitively answer some of the tantalising questions opened up by this pilot work.

Declaration of interest

T.C. appeared in the film A Human Experience. He has no substantive relationship with, and received no financial remuneration from, Rethink for participating in the film. Although T.C. devised and designed the study, he only participated in data collection at time points 1 and 2 for the control group and was not involved in data analysis.

Acknowledgements

We thank Mark Smith and Graeme Green for allowing us to employ their films in the trial, and all the mental health service users and professionals who appeared in the films.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.