The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidance on borderline personality disorder has wide implications for psychiatric services. 1 Key priorities outlined in this document include access to service, autonomy and choice, developing an optimistic and trusting relationship, and managing endings and transitions. General psychiatry is clearly drawn into the frame: community mental health teams (CMHTs) have a role in routine assessment, treatment and management of people with borderline personality disorder. The guidelines recommend that drug treatment should not be used specifically for borderline personality disorder or the individual symptoms or behaviour associated with the disorder (p. 297). The guidelines also emphasise ensuring equal access to services with reference to minority ethnic groups.

In response to local need and national priorities, a new service was commissioned by the primary care trust in the London borough of Tower Hamlets from September 2007. The DeanCross Personality Disorder Service forms part of the adult mental health services in East London NHS Foundation Trust. It is a dedicated non-forensic service for people with severe and moderate personality disorders. Referral criteria are personality disorder or accentuated personality traits which have a significant impact on the person or those around them. We offer predominantly group-based therapy with different levels of intensity (including a 3-days-a-week programme for 18 months and a 2-mornings-a-week programme for 2 years). The programme is particularly, but not exclusively, designed for individuals with borderline personality disorder.

The service follows a mentalisation-based treatment approach, Reference Bateman and Fonagy2 an evidence-based model for borderline personality disorder. Reference Bateman and Fonagy3-Reference Bateman and Fonagy6 Mentalising implies a focus on mental states in oneself or in others, particularly in explanations of behaviour. Reference Bateman and Fonagy7 Interrelated deficits associated with borderline personality disorder include identity formation, emotion regulation, impulsiveness and relationship problems. Problems in mentalisation may relate to any or all of these deficits.

Despite the growth of personality disorder services throughout the UK, a comprehensive literature search of the databases MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO, CINAHL and HMIC using the terms ‘personality disorder’ and ‘referral’ combined found that no previous studies on referrals to personality disorder services had been performed. However, one study was found which gave a qualitative overview of the setting up of a borderline personality disorder service and another published data specifically on the number of referrals and outcomes to an outreach personality disorder service. Reference Morant and King8,Reference Pretorius and Albeniz9

In this study we describe the profile and outcome of the first 100 individuals referred to DeanCross, using the NICE guidelines as a framework. We also present a case vignette to illustrate practical aspects of the NICE guidelines.

Method

We conducted a case record study of the first 100 consecutive referrals over a 12-month period from 1 September 2007 to 26 August 2008. In the absence of any standardised instrument, we developed a form to capture relevant data from referral information and the clinical records of assessments. The form was based on piloted case notes and covered all aspects addressed in the assessment process, including demographic details, personal history, presenting complaint, previous diagnosis, medication and previous treatment, and risk to self and others.

Results

Of the 100 individuals referred to the service, 60% were female; median age 36 years (there were 3 patients aged 18-20 and 97 aged 21-65). More than two-thirds were of White British or White Other ethnicity, with a smaller number whose ethnicity was recorded as Bangladeshi (9%) and British African/Caribbean (5%) (Fig. 1). The majority of those referred were unemployed (60%); 16 were referred from primary and 84 from secondary care.

Fig 1 Demographic profile of the study sample (n = 100).

Of those referred, nine individuals were not offered an assessment (six were already receiving or needed an alternative service and three were felt to be clearly not ready for an intensive psychological programme owing to extreme aggression or drug misuse). A quarter of those referred were accepted to the programme. Outcomes are shown in Table 1. The median number of assessment appointments per service user was 3, occurring over a mean of 26 weeks. This lengthy period of assessment was caused by a number of factors, including the individual's non-attendance at appointments, staff delays in offering appointments, and complexity of referrals. There was no significant difference in duration of assessment between those who engaged and attended the programme, and those who did not proceed.

Table 1 Outcomes of individuals referred to DeanCross personality disorder service

| Frequency | |

|---|---|

| Accepted | 25 |

| Ongoing owing to re-referral | 8 |

| Closed | |

| Individual did not want to proceed | 21 |

| Individual not ready | 12 |

| Consultation only | 9 |

| Did not arrive, no response | 8 |

| Service elsewhere | 7 |

| Out of area | 5 |

| Dissocial traits/aggression/drug use | 5 |

| Total | 100 |

Presenting complaints, as stated by the service users at first interview, are shown in Table 2, with difficulties with affect (21%) and difficulties with relationships (18%) being the most prevalent. Fifty-five individuals had some current form of self-harm. Of these, 35 had more than one form of self-harming. Combining both previous and present history of self-harm, cutting (44 patients) and overdosing (44 patients) was the most common. Sixty-seven individuals had used illicit substances, with 31 describing a current drug problem. The most commonly used drug was cocaine (41%), followed by cannabis (35%) and ecstasy (15%). Examination of alcohol use showed that 42 individuals have had a problem with alcohol misuse, of whom 27 still misused alcohol.

Table 2 Common presenting complaints in the study samplea

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Difficulties with affect | 43 (21) |

| Relationship difficulties | 36 (18) |

| Unknownb | 27 (13) |

| Anxiety | 22 (11) |

| Self-harm | 20 (10) |

| Anger | 18 (9) |

| Other | 11 (5) |

| Drug/alcohol misuse | 7 (3) |

| Isolation | 7 (3) |

| Self-image | 5 (2) |

| Intrusive thoughts/hallucinations | 5 (2) |

Regarding primary diagnoses, 48 individuals had a diagnosis of borderline personality disorder, 6 had another personality disorder, 7 had other diagnoses, which included obsessive-compulsive disorder, body dysmorphic disorder and psychotic disorders, and 37 had no diagnosis established owing to non-attendance or incomplete assessments. Diagnosis was based on referrer's previous diagnosis and confirmed by our service in cases of completed assessments according to ICD-10 criteria. 10

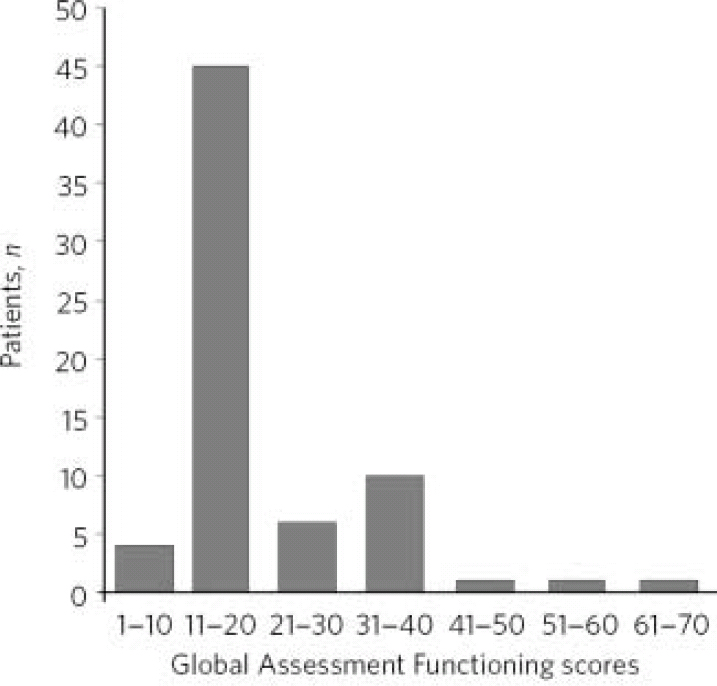

The Global Assessment Functioning Reference Endicott, Spitzer, Fleiss and Cohen11 scores are shown in Fig. 2, with the majority of individuals (66%) being scored between 11 and 20.

Fig 2 The Global Assessment Functioning scores in the study sample (n=68 owing to incomplete assessments or non-attendance).

Forty-four individuals had a previous forensic history. In terms of contact with the criminal justice system, 19 had contact with the police, 7 had contact with the courts, and 18 had served a sentence in prison; 27 had physically assaulted someone.

Prescription of psychotropic medication was common (51 individuals). Over a fifth of individuals (23%) were prescribed at least three psychotropics. Antidepressants and antipsychotics were the most frequently used psychotropic medication (54 and 36% respectively). Thirty of the 48 individuals diagnosed with borderline personality disorder were on psychotropic medications, of which only one was clearly presently indicated based on NICE guidelines (this person was on a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor for treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder). Just over a third of individuals (37%) had already received psychological treatment.

Case vignette

(The vignette is a composite of different individuals we have assessed in our service and describes a typical rather than a more severe case.)

Mr F, 25 years old and White British, was referred by his community mental health team (CMHT) with a diagnosis of borderline personality disorder. His main presenting complaint was repeated self-harm related to highly turbulent personal relationships. The relationship with his CMHT was also fraught. He felt overlooked and misunderstood by the CMHT who in turn felt frustrated by Mr F's cycle of rejecting all help and then telephoning the clinic to say he had self-harmed. He frequently attended his appointments intoxicated with alcohol and was threatening to staff at these times. The CMHT finally discharged him as they felt he was not ready to follow a consistent plan and work with the team. He was assessed by our service over a course of seven meetings over a period of 13 months. The prolonged assessment was related to Mr F's impulsiveness and extreme emotions (predominantly anger and suspiciousness) during the meetings. Mr F felt a strong need to control the meetings, resulting in much time being consumed by negotiating how to proceed in the encounters. He requested dialectical behavioural treatment, a service that is not locally available. The assessment confirmed a diagnosis of borderline personality disorder. At present, he has withdrawn from the assessment and we are trying to re-engage him.

Discussion

The personality disorder service referral population does not match the wider population of Tower Hamlets. A third of the borough is of Bangladeshi origin, 12 but in the referral population only 9% come from this group. Other ethnic minorities were more evenly represented. It may be that Bangladeshi groups are not recognised to have personality difficulties or judgements are being made about their non-psychological mindedness, or they are not seen to have a moderate to severe personality disorder, perhaps mirroring what has been found for common mental disorders for South Asian populations. Reference Bhui, Bhugra, Goldberg, Dunn and Desai13

The lengthy assessment period reflects both difficulties in engaging individuals who show extreme ambivalence to the service but also the difficulty of the service not losing the focus of the assessment given the complexity of the presentations.

Referrals broadly appear to be appropriate in regard to presenting complaint (including difficulties with affect, relationship problems, self-harm, proportion of individuals reaching caseness for borderline personality disorder, severity (Global Assessment Functioning scores indicate the low level of functioning of the majority of service users) and complexity (forensic history, substance misuse). Drug and alcohol problems were a frequent comorbidity. A quarter of individuals described current alcohol misuse, which might make working within an intensive psychological model difficult.

There is a high level of psychotropic prescribing in this patient group. In contrast, the NICE guidelines 1 for borderline personality disorder state there is no role for medications specifically for this condition.

Case vignette analysis

The case vignette illustrates difficulties systemically and in mentalising. Regarding systemic aspects, it shows difficulties in implementing NICE guidelines, particularly in terms of autonomy and choice. The person was keen to have dialectical behavioural treatment, which is not available in our borough. The hostile interaction between the person and the CMHT prevented the development of an optimistic and trusting relationship, making any smooth handling of endings and transitions difficult. The consultant psychiatrist in the CMHT believed that individuals with personality disorder had no place in the CMHT service, illustrating challenges in the recommendation that CMHTs have a role in the routine assessment, management and treatment of individuals with borderline personality disorder.

With regard to mentalising, the person experienced particular difficulties in accurately identifying the mental states of the clinicians assessing him, as shown in his extreme suspiciousness. Specific examples of deficits in mentalising shown included concrete thinking in which an internal reality was equated with external reality (in his case, ‘I feel you are against me and therefore that is true’) and over-generalising (‘All psychiatrists are the same - brutal and uncaring’).

Recommendations

Black and minority ethnic under-representation in referrals to the personality disorder service needs to be actively investigated. Although the service appears to be receiving appropriate referrals, we need to establish whether Black and minority ethnic individuals in particular are not being referred related to either patterns of healthcare-seeking in service users or under-recognition in clinicians. We have started networking with general practice surgeries known to have a high proportion of Bangladeshi patients and with local Black and minority ethnic groups. A research agenda is being established in collaboration with the Wolfson Institute (Queen Mary, University of London) to explore this.

Access to the service needs to be improved. We have developed less intensive treatments to engage individuals who are assessed as not being ready for the original programme. An example of this includes a brief, structured, manualised, mentalisation-based individual treatment, consisting of eight sessions at 2-weekly intervals.

The duration of the assessment period needs addressing. We have shortened intervals between appointments by planning in dates in advance rather than after each assessment meeting. We have also acknowledged that many of the assessments do require up to six meetings and have restructured them as therapeutic assessments and psychotherapeutic interventions in their own right (e.g. by giving a copy of our report and formulation to the patient and discussing it as part of the assessment).

Interventions to support psychiatrists in reviewing their prescribing practice regarding individuals with borderline personality disorder in line with NICE guidance are required and we are planning a series of workshops. In addition, we are addressing the inevitable organisational splits between services regarding management of individuals with personality disorder through a series of trust-wide stakeholder meetings to discuss implications of the NICE guidelines, and more locally through monthly clinical discussion groups and seminars.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.