The subject of place-of-safety legislation for people with mental disorders has long been a controversial topic. Compulsory powers given to the police under mental health legislation generally allow them to remove a person, where mental disorder is suspected, from a public place to arrange for compulsory assessment by mental health professionals. However, variation in practice around the UK is considerable, not least because of the differences in legislation that apply in Scotland compared with England and Wales. For many years, debate has focused on the type of place of safety that is used, the lack of information and level of understanding among professionals about the process of compulsory assessment, Reference Jones and Mason1 and patients’ negative experiences. The continued use of police cells as a place of safety has been repeatedly criticised in the literature by all parties for at least the past 20 years. Reference Bean, Bingley, Bynoe, Faulkner, Rassaby and Rogers2-Reference Cherrett4

Despite widely similar reports and issues being raised, particularly with regard to Section 136 of the Mental Health Act 1983 (England and Wales), little progress was made until a report by the Independent Police Complaints Commission was published in 2008, Reference Docking, Grace and Bucke5 showing that two-thirds of the 17400 people detained under Section 136 in 2005-2006 were held in a police cell. In response, the Royal College of Psychiatrists set up a multi-agency group that recommended aiming to improve and standardise the quality and documentation of care received by patients under Section 136 in England. 6 In 2008 a pilot project was implemented in three centres to trial the recommendations made before incorporating the practices into the Code of Practice (England) for the Mental Health Act 1983. 6

The corresponding situation in Scotland is unknown. There is a dearth of specific reports about place-of-safety legislation in Scotland in the literature. Reference Begum, Helliwell and Mackay7,Reference Graham8 The Mental Health (Care and Treatment) (Scotland) Act 2003 was introduced in October 2005, and supported by a code of practice, 9-11 which included recommendations made by the Millan Committee. 12 Under Section 297 of this act:

-

• the police can remove, to a place of safety, a person whom they suspect to be mentally disordered and in need of immediate care or treatment;

-

• medical examination and any care and treatment can be arranged;

-

• the maximum detention period is 24 h compared with 72 h previously;

-

• health boards are put under legal obligation to provide a place of safety that is not a police station, other than in exceptional circumstances;

-

• police constables are under duty to inform several parties, including the Mental Welfare Commission for Scotland, of their use of the legislation;

-

• a POS1 form was made available on the Scottish Executive website (www.scotland.gov.uk/Resource/Doc/1094/0052164.pdf) to document use of legislation, 10 but it is non-mandatory. A POS1 requires demographics, time, date and circumstance of removal and the address of the place of safety to be recorded.

In 2007 the Mental Welfare Commission for Scotland confirmed that it expected to be notified of all place-of-safety orders in Scotland. 13 Despite this, the Commission's 2008-2009 report describes a marked variation in places of safety notified to the Commission (Table 1). These numbers imply a range of notification rates from 0.35 to 26.6 places of safety notified per 100 000 people served by a police force. 14-20

Table 1 Places of safety notified to the Mental Welfare Commission for Scotland 1 April 2008 to 31 March 2009

| Was place of safety a police station? | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Police force | No | Unknown | Yes | Total |

| Central Scotland | 1 | 1 | ||

| Fife | 13 | 1 | 14 | |

| Grampian | 56 | 1 | 1 | 58 |

| Lothian and Borders | 9 | 1 | 10 | |

| Northern | 70 | 8 | 2 | 80 |

| Strathclyde | 23 | 2 | 25 | |

| Tayside | 4 | 4 | ||

| Total | 176 | 9 | 7 | 192 |

In 2004, NHS Highland Acute Mental Health Services introduced a joint protocol (Appendix 1) with the Inverness Area Command of Northern Constabulary to clarify the documentation and procedure to be followed by both agencies when using place-of-safety legislation. Inverness Area Command is one of eight area commands under Northern Constabulary. New Craigs Hospital (the only acute psychiatric hospital in NHS Highland at the time) was agreed as the place of safety for Inverness Area Command. Other area commands have different arrangements.

Appendix 1 Section 297 joint protocol flowchart

CPN, community psychiatric nurse; IPCU, intensive psychiatric care unit; NCH, New Craigs Hospital, Inverness; NOK, next of kin; PNC, Police National Computer; SCRO, Scottish Criminal Record Office.

Adherence to the protocol was audited in 2004-2005 under the Mental Health (Scotland) Act 1984 legislation. This indicated that documentation was completed well but amendments could be made to improve the quality of information about referrals. A re-audit a year later was also recommended. Around this time the Mental Health (Care and Treatment) (Scotland) Act 2003 was implemented. It was therefore agreed that the POS1 replace local documentation and that the re-audit look at the quality of information about the referrals contained in the new format of the POS1.

We aimed to present the key findings of the completed audit cycle in the context of the quality of information provided by the police on the POS1. During this process, however, we came across further information that we had not planned for in the initial audit design. Therefore, we also report our rates of notification to the Mental Welfare Commission for Scotland (as per the standard set out in the Code of Practice) and local completion rates of POS1. Some other relevant findings relating to the assessment process are also presented.

Method

A prospective audit was carried out from 1 July 2007 to 30 June 2008. Along with the POS1, a locally developed audit form (Section 297 form) was completed for all referrals made by the police to New Craigs Hospital. Nursing staff in the intensive psychiatric care unit (IPCU), where all referrals are seen, collected both forms and sent them to the audit team. To ensure that all referrals were included, the doctor's admission book and the IPCU ward diary were checked regularly for records of Section 297 referrals. Where possible, missing data were traced through clinical notes, ward admission books and medical records databases.

To determine the completeness of our data, we contacted the Mental Welfare Commission for Scotland.

Information from the POS1 under the heading ‘The circumstances giving rise to the removal of the aforementioned person to a place of safety were—’ was collected to establish the quality of information about referrals.

Results

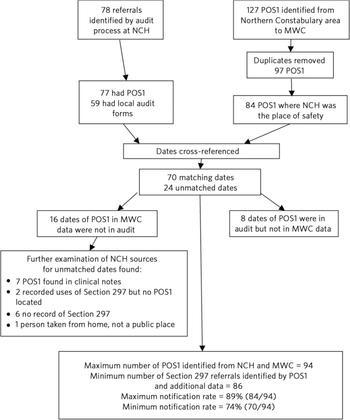

Figure 1 shows the numbers of forms collected by the audit team and by the Mental Welfare Commission for Scotland. It should be noted that cross-referencing dates was the only means available to us to identify POS1 forms collected by both us and the Mental Welfare Commission for Scotland. As this method is not robust enough to confirm whether the POS1 forms identified by New Craigs Hospital and the Mental Welfare Commission for Scotland account for the same event or different events, we feel that we should not speculate as to the reason for these differences. The total number of POS1 identified is therefore a maximum.

Fig 1 Breakdown of numbers of forms collected by the audit team and the Mental Welfare Commission for Scotland. MWC, Mental Welfare Commission for Scotland; NCH, New Craigs Hospital, Inverness.

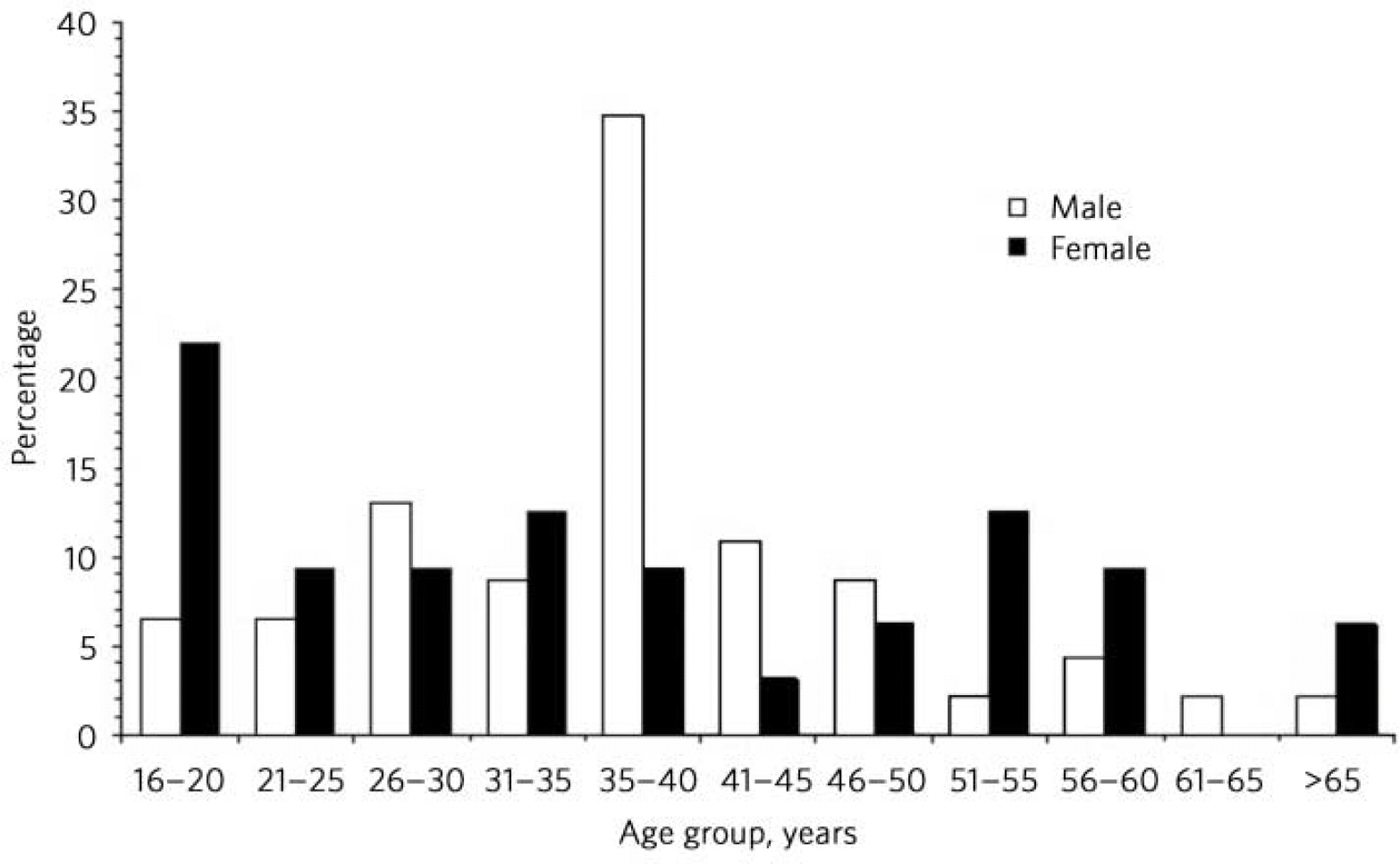

Of all patients referred, 46 (59%) were male and 32 (41%) were female. The average age of the patients was 38 years (range 16-84). Age according to gender is shown in Fig. 2.

Fig 2 Age of patients referred under Section 297, by gender.

There was little variation in the number of referrals brought in by day of the week. A peak in arrival time between 21.00 h and 01.00 h accounted for 41% of all referrals.

The average waiting time to interview was 36 min (range 0-225). Fifty-four per cent of patients were seen within 30 min and 96% within 2 h. The mean length of assessment was 75 min (maximum 195 min).

In terms of the outcome of the assessment, 9% of patients were admitted involuntarily and 44% were admitted voluntarily. A total of 47% were not admitted: 62% of these patients were able to go home, 24% were picked up by the police and 14% had other arrangements made (e.g. earlier appointment with a consultant psychiatrist).

For patients who were admitted, the mean length of admission was 11.8 nights (range 0-61); 37% of those admitted were in hospital for more than 1 week and 22% for more than 4 weeks.

Qualitative analysis of the written information given on the POS1 is listed for patients who were admitted and patients who were not admitted and includes the following:

-

• location, time and date of police contact;

-

• presence of current missing person report;

-

• informants present and the history they gave the attending officers;

-

• observed specific behaviour or content of dialogue considered to be caused by mental disorder;

-

• emotions displayed raising concern;

-

• general behaviour of the individual during contact at location and en route to hospital;

-

• verbalised suicidal intent;

-

• known recent/previous suicide attempts;

-

• evidence at location and on patient of self-harm/suicidal behaviour often indicating severity, e.g. poems about death, razor blades, knives, ligature marks on neck;

-

• level of violence witnessed/reported and whether it was escalating or de-escalating;

-

• social circumstances;

-

• social stressors identified.

For patients who were not admitted, the information was weighted towards social information regarding support from family and friends and other agencies already involved. For patients who were admitted, the information was weighted towards evident risk of self-harm or violence, appearance of the patient, and the patient's psychiatric and medical history.

From the 77 forms completed, it was noted that 41 forms raised concerns about suicidal or self-harming behaviour. Of these, 26 patients (63%) were not admitted and 15 patients (37%) were admitted.

Discussion

This audit was originally designed to look at the quality of information about referrals and local adherence to the joint protocol in the context of completing an audit cycle. The introduction of the POS1 achieved the first objective from the point of view of the police officers. The local Section 297 audit forms achieved the second objective. However, the Section 297 form did not collect information about subsequent diagnoses, presence of drug and alcohol use, or specific information about suicide or self-harm. In hindsight this may have been a missed opportunity. However, this also seems likely to be a study in itself, beyond the scope of an audit of a protocol.

Qualitative analysis of the POS1 revealed that appropriate referral information was given by police officers. Despite no additional training of the Inverness Area Command officers, they consistently provided information that easily falls into the categories used in a standard psychiatric history. This seems to be in direct contrast to frequent calls in the literature for improved police training in relation to the Mental Health Act 1983. 21-Reference Lynch, Simpson, Higson and Grout23 Could the establishment of robust joint protocols at a local level reduce the need for further in-depth training?

In the process of our audit, we found a general absence of concrete information about how Section 297 power is used and reported on in Scotland. This became our focus as we completed the audit. The Mental Welfare Commission for Scotland initially provided us with figures containing duplications. The Commission also reports a marked variation in numbers notified across Scotland (Table 1). It states that ‘We know that we are not always informed when these orders are used’ and figures ‘are indicative at best and should not be regarded as an accurate reflection of practice’ (A. Aiton, personal communication, 2010).

We are concerned that this variation (reported for the year after our audit) reflects an unacceptable variation in patient care. As stated earlier, these numbers imply a range of notification rates, from 0.35 to 26.6 places of safety notified per 100 000 people. 14-20 Such a wide range in notification rates must have a number of driving factors. Do some police forces not routinely inform the Mental Welfare Commission for Scotland of the use of Section 297 (despite being obliged to do so under legislation) by means of the POS1 or any other method? Is there still inadequate healthcare provision, meaning that the police remove a person to custody instead of a place of safety, using the police surgeon as a means to facilitate assessment? If this is the case, then not only is place-of-safety legislation not used but also there is no way to record this. Do other health boards implement their responsibilities under the Mental Health (Care and Treatment) (Scotland) Act 2003 by clearly structured or ad hoc means? There is a lack of information to answer these questions in the literature.

Our joint protocol, requiring use of the POS1 and subsequent notification to the Mental Welfare Commission for Scotland, resulted in 70 (minimum) to 84 (maximum) Section 297 referrals being notified to the Mental Welfare Commission for Scotland by way of the POS1 forms. This gives evidence to other health boards that establishing a joint protocol with their own police force should facilitate consistent implementation of the legislation for their population. Making the use of POS1 mandatory as part of our protocol has been initially successful and assists the transfer of responsibility from one agency to another as opposed to being a paperwork burden for police officers. Indeed, Fife Constabulary has agreed use of POS1 in its place-of-safety standard operating procedures published in August 2010. 24 We believe use of POS1 across Scotland would dramatically improve notification of the Mental Welfare Commission for Scotland and standardise patient care.

The difference in age and gender of the groups presenting may be an interesting starting point for further research, particularly if a more powerful data-set were collected. More detailed knowledge of the behaviour of the two groups and diagnosis on medical assessment may help to identify high-risk groups.

Concerns have been raised nationally about the staffing of so-called ‘places of safety units’. 3 The peak in number of referrals between 21.00 h and 01.00 h could add to this concern. As our place of safety is a hospital, there is generally more capacity to respond to such clinical demands.

The mean waiting time to be assessed is well within the 4-hour waiting time stipulated for accident and emergency departments 25 and also meets the locally agreed standard for time to be seen by a doctor. The protocol seems to speed up compulsory assessment and validates the Millan Committee recommendation to decrease the time period of detention under the new legislation.

In terms of admission length, a significant number of referrals remained in hospital for over a month. This could suggest that the police have a unique opportunity to identify and refer individuals with mental health needs who have not been picked up elsewhere in the health or social care systems. To confirm this, further information regarding the admission, discharge and diagnosis would be required.

This audit, intended to study local practice, has revealed a serious absence of information regarding application of place-of-safety legislation at a national level. Locally we have established that a joint protocol and standard use of the POS1 form can go a significant way to addressing this, although further work needs to be done to imbed these procedures in practice. The joint protocol is to be revised to accomplish this and then audited again. Nationally, the Mental Welfare Commission for Scotland will remain unable to describe the use and misuse of Section 297 accurately until all health boards and police forces have a consistent procedure in place for reporting its use to them. Meanwhile, vulnerable people may not receive efficient, equitable or appropriate care.

Acknowledgements

We thank the nursing and medical staff of Affric Ward, New Craigs Hospital; Dr Andy Gajda, New Craigs Hospital; Rob Polson, Subject Librarian, Highland Health Sciences Library; and the Mental Welfare Commission for Scotland.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.